ECE-GY 6143, Spring 2020

Reinforcement Learning

Through this course, we have primarily focused on supervised learning (building a prediction function from labeled data), and briefly also discussed unsupervised learning (discovering structure in unlabeled data). In both cases, we have assumed that the data to the machine learning algorithm is static and the learning is performed offline. Even more troublesome is the following fact: in the real world, the data that is available is often influenced by previous predictions that you have made. (Think, for example, of stock markets.)

A third mode of machine learning is captured by reinforcement learning (RL). The field of RL is broad and we will only be able to scratch the surface. But several of the recent success stories in machine learning are rooted in advances in RL – the most high profile of them are Deepmind’s AlphaGo and OpenAI’s DOTA 2 AI, which were able to beat the world’s best human players in Go and DOTA. These AI agents were able to learn winning strategies entirely automatically (albeit by leveraging massive amounts of training data; we will discuss this later.)

To understand the power of RL, consider – for a moment – how natural intelligence works. An infant presumably learns by continuously interacting with the world, trying out different actions in possibly chaotic environments, and observing outcomes. In this mode of learning, the input(s) to the learning module in the infant’s brain is decidedly dynamic; learning has to be done online; and very often, the environment is unknown before hand.

For all these reasons, the traditional mode of un/supervised learning does not quite apply, and new ideas are needed.

A quick aside: the above questions are not new, and study of these problems actually classical. The field of control theory is all about solving optimization problems of the above form. But the approaches (and applications) that control theorists study are rather different compared to those that are now popular in machine learning.

Setup

We will see that RL is actually “in-between” supervised and unsupervised learning.

The basis of RL is an environment (modeled by a dynamical system), and a learning module (called an agent) makes actions at each time step over a period of time. Actions have consequences: actions periodically lead to reward, or penalty (equivalently, negative reward). The goal is for the agent to learn the best policy that maximizes the cumulative reward. All fairly intuitive!

Here, the “best policy” is application-specific – it could refer to the best way to win a game of Space Invaders, or the best way to allocate investments across a portfolio of stocks, or the best way to navigate an autonomous vehicle, or the best way to set up a cooling schedule for an Amazon Datacenter.

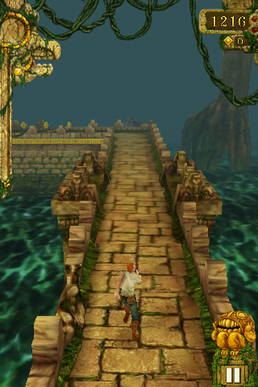

All this is a bit abstract, so let us put this into concrete mathematical symbols, and interpret them (as an example) in the context of the classic iOS game Temple Run, where your game character is either Guy Dangerous or Scarlett Fox and your goal is to steal a golden idol from an Aztec temple while being chased by demons. (Fun game. See Figure 1.) Here,

- The environment is the 3D game world, filled with obstacles, coins, etc.

- The agent is the player.

- The agent receives a sequence observations (in the form of e.g. image pixels) about the environment.

- The state at time $t$, $s_t$, is the instantaneous relevant information of the agent (e.g. the 2D position and velocity of the player).

- The agent can choose an action, $a_t$, at each time step $t$ (e.g. go left, go right, go straight). The next state of the game is determined by the current state and the current action: \(s_{t+1} = f(s_t, a_t) .\) Here, $f$ is the state transition function that is entirely determined by the environment. In control theory, we typically call this a dynamical system.

- The agent periodically receives rewards (coins/speed boosts) or penalties (speed bumps, or even death!). Rewards are also modeled as a function of the current state and action, $r(s_t,a_t)$.

- The agent’s goal is to decide on a strategy (or policy) of choosing the next action based on all past states and actions: $s_t, a_{t-1}, s_{t-1}, \ldots, s_1, a_1, s_0, a_0$. The sequence of state-action pairs $\tau_t = (s_0, a_0, a_1, s_1, \ldots, a_t, s_t)$ is called a trajectory or rollout. Typically, it is impractical to store and process the entire history, so policies are chosen only over a fixed time interval in the past (called the horizon length $L$).

So a policy is simply a function $\pi$ that maps $\tau$ to $a_t$. Our goal is to figure out the best mapping function (in terms of maximizing the rewards). Such an optimization is well suited to machine learning tools we already know! Pose the cumulative negative reward as a loss function, and minimize this loss as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} \text{minimize}~&R(\tau) = \sum_{t=0}^{L-1} - r(s_t, a_t), \\ \text{subject to}~&s_{t+1} = f(s_t,a_t) \\ & a_t = \pi(\tau_t) . \end{aligned}\]OK, this looks similar to a loss minimization setting that we are all familiar with. We can begin to apply any of our optimization tools (e.g. SGD) to solve it. Several caveats, however, and we have to be more precise about what we are doing.

First, what are the optimization variables? We are seeking the best among all policies $\pi$ (which, above, are defined as functions from trajectories to actions), so this means that we will have to parameterize these policies somehow. We could imagine this to be a linear model, or kernel model, or a deep neural network (the last one opens the door to a sub-field of RL called deep reinforcement learning). For now, let’s just stay simple and consider linear policies.

Second, what are the “training samples” provided to us and what are we trying learn? The key assumptions in RL is that everything in the general case is probabilistic:

- the policy is stochastic. So what $\pi$ is actually predicting from a given trajectory is not a single action but a distribution over actions; more favorable actions get assigned higher probability and vice versa.

- the environment’s dynamics, captured by $f$, can be stochastic.

- the reward function itself can be stochastic.

The last two assumptions are not critical – for example, in simple games, the dynamics and the reward are deterministic functions; but not so in more complex environments, such as the stock market – but the first one (stochastic policies) is fundamental in RL. This also hints to why we are optimizing over policies in the first place: if there was no uncertainty and everything was deterministic, an oracle could have designed an optimal sequence of actions for all time before hand. (In older Atari-style or Nintendo video games, this could indeed be done and one could play an optimal game pretty much from memory).

Since policies are probabilistic, they induce probability distribution over trajectories, and hence the cumulative negative reward is also probabilistic. So to be more precise, we will need to rewrite the loss in terms of the expected value over the randomness:

\[\begin{aligned} \text{minimize}~&\mathbb{E}_{\pi(\tau)} R(\tau) = \sum_{t=0}^{L-1} - r(s_t, a_t), \\ \text{subject to}~&s_{t+1} = f(s_t,a_t) \\ & a_t = \pi(\tau_t),~\text{for}~t = 0,\ldots,L-1. \end{aligned}\]This probabilistic way of thinking makes the role of ML a bit more clear. Suppose we have a yet-to-be-determined policy $\pi$. We pick a horizon length $L$, and execute this policy in the environment (the game engine, a simulator, the real world, \ldots) for $L$ time steps. We get to observe the full trajectory $\tau$ and the sequence of rewards $r(s_t,a_t)$ for $t=0,\ldots,L-1$. This pair is called a training sample. Because of the randomness, we simulate multiple such rollouts, and compute the cumulative reward averaged over all such rollouts, and adjust our policy parameters until this expectation is maximized.

We now return to the first sentence of this subsection: why RL is “in-between” supervised and unsupervised learning. In supervised learning we need to build a function that predicts label $y$ from data features $x$. In unsupervised learning there is no separate label $y$; we typically wish to predict some intrinsic property of the dataset of $x$. In RL, the “label” is the action at the next time step, but once taken, this action becomes part of the training data and influences the subsequent action. This issue of intertwined data and labels (due to the possibility of complicated feedback loops across time) makes RL considerably more challenging.

Policy gradients

Let us now discuss a technique to numerically solve the above optimization problem. Basically, it will be akin to ‘trial-and-error’ – sample a rollout with some actions; if the reward is high then make those actions more probable (i.e., “reinforce” these actions), and if the reward is low then make those actions less probable. In order to maximize expected cumulative rewards, we will need to figure out how to take gradients of the reward with respect to the policy parameters.

Recall that trajectories/rollouts $\tau$ are a probabilistic function of the policy parameters $\theta$. Our goal is to compute the gradient of the expected reward, $\mathbb{E}_{\pi(\tau)} R(\tau)$ with respect to $\theta$. To do so, we will need to take advantage of the log-derivative trick. Observe the following fact:

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial}{\partial \theta} \log \pi(\tau) &= \frac{1}{\pi(\tau)} \frac{\partial \pi(\tau)}{\partial \theta},~\text{i.e.} \\ \frac{\partial \pi(\tau)}{\partial \theta} &= \pi(\tau) \frac{\partial}{\partial \theta} \log \pi(\tau) . \end{aligned}\]Therefore, the gradient of the expected reward is given by:

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial}{\partial \theta} \mathbb{E}_{\pi(\tau)} R(\tau) &= \frac{\partial}{\partial \theta} \sum_{\tau} R(\tau) \pi(\tau) \\ &= \sum_\tau R(\tau) \frac{\partial \pi(\tau)}{\partial \theta} \\ &= \sum_\tau R(\tau) \pi(\tau) \frac{\partial}{\partial \theta} \log \pi(\tau) \\ &= \mathbb{E}_{\pi(\tau)} [R(\tau) \frac{\partial}{\partial \theta} \log \pi(\tau)]. \end{aligned}\]So in words, the gradient of an expectation can be converted into an expectation over a closely related quantity. So instead of computing this expectation, like in SGD we sample different rollouts and compute a stochastic approximation to the gradient. The entire pseudocode is as follows.

Repeat:

-

Sample a trajectory/rollout $\tau = (s_0, a_0, s_1, \ldots, s_L)$.

-

Compute $R(\tau) = \sum_{t=0}^{L-1} - r(s_t, a_t)$

-

$\theta \leftarrow \theta - \eta R(\tau) \frac{\partial}{\partial \theta} \log \pi(\tau)$

There is a slight catch here, since we are reinforcing actions over the entire rollout; however, actions should technically be reinforced only based on future rewards (since they cannot affect past rewards). But this can be adjusted by suitably redefining $R(\tau)$ to sum over the $t^{th}$ time step until the end of the horizon.

That’s it! This form of policy gradient is sometimes called REINFORCE.

In the above algorithm, notice that we never require direct access to the environment (or more precisely, the model of the environment, $f$) – only the ability to sample rollouts, and the ability to observe corresponding rewards. This setting is therefore called model-free reinforcement learning. A parallel set of approaches is model-based RL, which we won’t get into.

Connection to random search

In the above algorithm, in order to optimize over rewards, observe we only needed to access function evaluations of the reward, $R(\tau)$, but never its gradient. This is in fact an example of derivative free optimization, which involves optimizing functions without gradient calculations.

Another way to do derivative free optimization is simple: just random search! Here is a quick introduction. If we are minimizing a loss function $f(\theta)$, recall that gradient descent updates $\theta$ along the negative direction of the gradient:

\[\theta \leftarrow \theta - \eta \nabla f(\theta) .\]But in random search, we pick a random direction $v$ to update $\theta$, and instead search for the (scalar) step size that provides maximum decrease in the loss along that direction. The pseudocode is as follows:

- Sample a random direction $v$

- Search for the step size (positive or negative) that minimizes $f(\theta + \eta v)$. Let that step size be $\eta_{\text{opt}}$.

- Set $\theta \leftarrow \theta + \eta_{\text{opt}} v$.

So, the gradient of $f$ never shows up! The only catch is that we need to do a step size search (also called line search). However, this can be done quickly using a variation of binary search. Notice the similarity of the update rules (at least in form) to REINFORCE.

Let us apply this idea to policy gradients. Instead of the log-derivative trick, we will simply assume deterministic policies (i.e., a particular choice of policy $\theta$ leads to a deterministic rollout $\tau$) use the above algorithm, with $f$ being the reward function. The overall algorithm for policy gradient now becomes the following.

Repeat:

-

Sample a new policy update direction $v$.

-

Search for the step size $\eta$ that minimize $R(\theta + \eta v)$.

-

Update the policy parameters $\theta \leftarrow \theta + \eta v$.

Done!